5 reasons I don’t care for hip-hop

Stephen H. Provost

I’d rather do a lot of things than listen to hip-hop. That doesn’t make it bad; it just means I don’t like it.

Read MoreUse the form on the right to contact us.

You can edit the text in this area, and change where the contact form on the right submits to, by entering edit mode using the modes on the bottom right.

PO Box 3201

Martinsville, VA 24115

United States

Stephen H. Provost is an author of paranormal adventures and historical non-fiction. “Memortality” is his debut novel on Pace Press, set for release Feb. 1, 2017.

An editor and columnist with more than 30 years of experience as a journalist, he has written on subjects as diverse as history, religion, politics and language and has served as an editor for fiction and non-fiction projects. His book “Fresno Growing Up,” a history of Fresno, California, during the postwar years, is available on Craven Street Books. His next non-fiction work, “Highway 99: The History of California’s Main Street,” is scheduled for release in June.

For the past two years, the editor has served as managing editor for an award-winning weekly, The Cambrian, and is also a columnist for The Tribune in San Luis Obispo.

He lives on the California coast with his wife, stepson and cats Tyrion Fluffybutt and Allie Twinkletail.

Ruminations and provocations.

Filtering by Tag: hip-hop

I’d rather do a lot of things than listen to hip-hop. That doesn’t make it bad; it just means I don’t like it.

Read MoreOK, Millennial.

My first point: There should be a comma after “OK” in “OK, Boomer.” Otherwise, you’re saying Boomers are OK, which is not what I think you mean to suggest.

If I’ve got this straight, you’re trying to say we’re out of touch, that our ideals are flawed, that we don’t know what the hell we’re talking about. Right?

Fine. Now, get off my lawn!

Wait. Hold on a minute. Let’s start again.

I said “we” with a couple of caveats. First, I’m what you might call a Barely Boomer. I was born in 1963, a year before the arbitrary generational cutoff that would have sorted me (just as arbitrarily) into Generation X. I was born to late for malt shops and even for the hippie movement. But too soon for the “me” generation of the Reagan ’80s.

So, I don’t really fit into your neat little categories. And that’s the point of my second caveat: Most of us don’t. Neither do most of you, if you’re honest with yourself, because stereotypes are a crutch, and a rather poor one, at that. Some “Boomers” really are OK by your standards: We agree with you on a lot of things; and some of you probably agree with us more often than you’d care to admit.

But one thing all generations seem to have in common is the way we age. When we’re young — say in our teens to our early 30s — we soak up stuff and make it ours. Our music. Our fads. Our pop culture. Our slang. We use it to help define who we are.

Then, however, the world moves on and we feel a little less at home. That’s normal. Imagine growing up on one place, calling it home for most of your life, then moving all the way across the country in your 40s. You may appreciate your new surroundings; they may even be objectively more comfortable and better suited to your needs. But you’ll always have a certain wistfulness about where you grew up (assuming you had a halfway decent childhood).

When our fads and music and lingo and culture gives way to the next generation’s, that’s how we feel. It’s how our parents felt, and it’s how you’ll feel, too. We feel a little out of place. That’s not generational. It’s human. You’ll feel the same way when you find the next generation creating its own distinct place in the world.

I got to thinking about all this listening to a satellite radio station today. It was playing “oldies” from different generations: I remembered some fondly from my childhood, but I remembered others just as fondly because my parents had enjoyed them and shared them with me.

Now, when I was a kid, I’d close the door to my room and crank up KISS or Aerosmith, bands my parents had no affinity for whatsoever. My dad was into the Limeliters and the Kingston Trio. My mom liked big band stuff. They both enjoyed Perry Como and Bing Crosby. I didn’t listen to that stuff in my room, but when Christmas specials came on TV featuring crooners from an earlier generation, I watched. And I enjoyed them.

Because my parents found something to like there, I may have decided, subconsciously, that it was worth at least giving it a chance. Or maybe, because I grew up in a stable, loving home, I came to associate my parents’ tastes with that feeling of stability and comfort. A lot of kids who came from broken or abusive homes probably don’t want anything to do with their parents’ culture, because to them, it represents pain and struggle. That’s understandable.

Still, it doesn’t mean you ought to dismiss that entire generation, any more than an older generation should dismiss you. It would be easy for me to hold you responsible for the “death of rock and roll” at the hands of hip-hop and boy bands, because I miss what I grew up with, what made me feel at home when I was forming my own identity.

But that doesn’t mean I get to act dismissive of your culture, to the extent that it appears, on the surface to be different than mine. Because, guess what? Each of us has just as much right to our cultural comfort level as the other. And we that has to be OK. Otherwise, we’ll ignore what we have in common: the desire to create, cultivate and celebrate our own identities – and cling to them as we grow older. You’ll do that, too.

So did my parents.

They’re gone now, unfortunately. And I miss them both. When Moon River comes on the radio these days, I don’t roll my eyes and complain about their generation’s pathetic taste in music. I think about how great it was that they could enjoy something that was uniquely theirs. It isn’t uniquely mine, but because they loved it, I can at least appreciate it. Because I loved them. I also realized I could learn something from them — and I can learn something from the younger generation, too.

I may never love hip-hop, and you may never get Aerosmith. Still, hip-hop pioneers Run-DMC had a monster hit with a remake of an Aerosmith song called Walk This Way that actually featured members of Aerosmith. It wasn’t the first time something like that had happened, either. Back in the early 1970s, Bing Crosby and David Bowie sang a duet of The Little Drummer Boy. If anything, that was even more improbable.

So maybe, instead of me shouting, “Get off my lawn,” and you scoffing, “OK, Boomer,” we should try singing a metaphorical duet. Neither one of us has to give up our identity to appreciate a different perspective. And each of us might find there’s a lot more to the other than the stereotypes we’ve created in our own heads.

OK, Millennial?

Stephen H. Provost is the author of Pop Goes the Metal: Hard Rock, Hairspray, Hooks & Hits, chronicling the evolution of pop metal from its roots in the 1960s through its heyday as “hair metal” in the 1980s and beyond. It’s available on Amazon.

What happened to rock ’n’ roll?

Elvis Presley and the Beatles were larger-than-life icons who created transcendent music, but a half-century after Beatles released their signature “White Album,” the genre seems anything but transcendent.

In his book Twilight of the Gods, Steven Hyden suggests that classic rock began with the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967 and ended with Nine Inch Nails The Fragile in 1999. (Apparently, NIN’s previous album title, The Downward Spiral, had been prophetic.) The model makes as much since as any, although I might push the death of the genre to 2003’s American Idiot by Green Day. but regardless, the question remains: Why did a genre of music that prided itself on burning out, instead just fade away?

Jimmy Page playing with Led Zeppelin in Chicago, mid-1970s.

For a while, rock looked invincible. It survived the onslaught of disco, which dominated radio in the late 1970s only to come crashing down at the end of that decade. But disco was ill-equipped to challenge rock ’n’ roll, because it was a different kind of animal.

Disco was all about white pants suits, Studio 54, excess and hedonism. It was jet-setting on a dancefloor. Rock, at its core, had never been about any of that. It had always been about rebellion, so when disco got too popular, rock ’n’ roll was equipped to fight back with bare knuckles and no holds barred. Rockers wore “Death to Disco” T-shirts to school, and in July of 1979, thousands of disco albums were blown up on Disco Demolition Night at Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

It was the beginning of the end for disco, but it also showcased the limitations of rock. As time passed, the music revolution of the 1960s lost its edge. Zeppelin broke up. The Who launched a seemingly endless series of farewell tours. The hope of a Beatles reunion died on December 8, 1980. Queen ended its self-imposed ban on synthesizers. KISS took off its makeup.

The music itself became more closely associated with middle-aged, middle-class nostalgia and aging hipsters than with anything close to the cutting edge. Seattle-based grunge gave it a brief jolt in the early ’90s, but it was only a temporary reprieve. First punk (in the late ’70s and early ’80s) then rap became the music of real rebellion, and rock was left to relive past glories on the fair circuit and classic rock radio.

Even new bands are following the same old formula. The Struts sound a lot like Queen with a dash of Oasis. Greta Van Fleet sounds like Zeppelin. As good as their music might sound (and it does sound good to classic rock aficionados like yours truly), it’s following a familiar template rather than attempting to create something groundbreaking, the way NIN did with The Fragile or Green Day did with American Idiot.

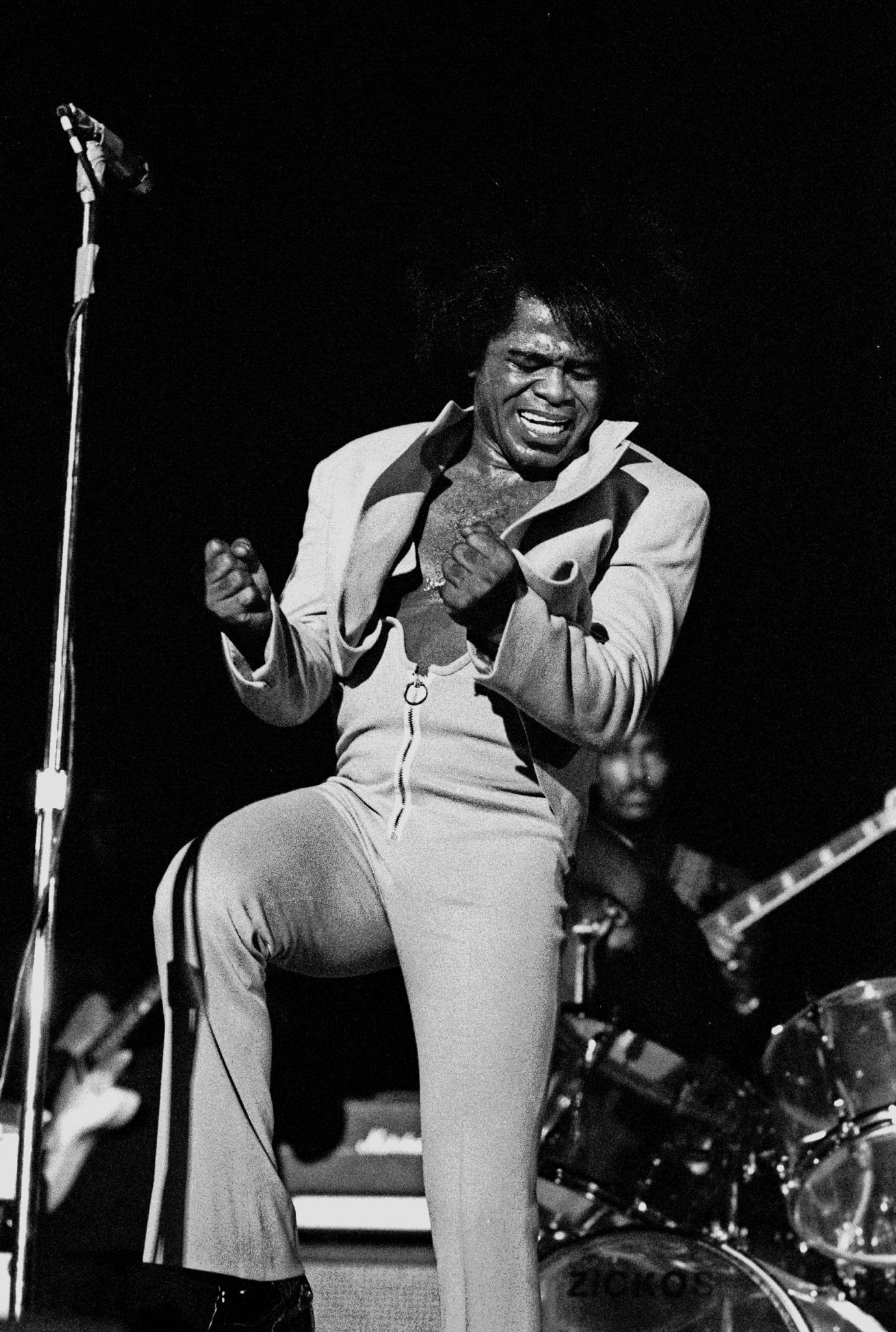

James Brown, Hamburg, 1973.

That’s a fairly standard explanation for the decline of rock, but there’s something more fundamental than decaying relevance and generational change at work here. There’s musical re-segregation. Rock ’n’ roll was the product of a nation getting ready to integrate black and white cultures. Elvis’ first number one single, Heartbreak Hotel, hit the charts barely two months after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Elvis and other white artists brought black rhythm and blues into the mainstream. The British Invasion is a misnomer: The blues invaded Britain first, then was sent back to the States courtesy of the Stones, the Animals, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall, Eric Clapton and others. Soon, black performers themselves were also in the spotlight via Motown, James Brown, the Supremes, the Miracles, Chuck Berry, et. al.

But white performers didn’t just borrow – or, in many cases, steal – R&B. They fused it with country, western swing and rockabilly to form something entirely new that was a reflection of a society experimenting with integration after decades of bigotry. Jackie Robinson had integrated baseball. Kenny Washington had integrated football. Brown v. Board of Education had integrated schools.

Now it was music’s turn. Rock ’n’ roll was to music what Brown was to legal precedent: It upended everything. But today, it barely survives.

The emergence of rap/hip-hop didn’t stop it, initially at least. Blondie recorded Rapture in 1980, Run-DMC covered Aerosmith’s Walk This Way five years later (with Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry guesting on the track). Kid Rock’s Devil Without a Cause in 1998 was an amalgam of good ol’ boy country music and inner-city rap that worked to the tune of 14 million in sales. Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory in 2000 has sold 30 million copies and remains the best-selling rock album of the new millennium.

The late Chester Bennington of Linkin Park, performing in 2014.

But as the music industry became fragmented, the segregation of the pre-Elvis era began to reassert itself. As rock went into decline, listeners turned to either hip-hop or rejuvenated (and more electrified) country music. Some hip-hop artists incorporated or sampled elements of rock, and some country artists did the same, but these days, rock tends to be the seasoning rather than the main ingredient. Most country fans have no use for hip-hop, and most hip-hop fans disdain country.

This new musical segregation reflects the nation at large. It’s not just about race. More fundamentally, the growing musical dichotomy reflects the widening cultural and political gap between urban and rural realities, a growing mutual isolation (and distrust) fed by an increased boutique approach to the arts.

Just as access to specialized news outlets has furthered the divide between liberals and conservatives, the same development has widened the gap between rural and urban artistic expression. The more easily we can get our ears on something we like, the more likely we are to ignore or disparage something that sounds foreign, and that’s just what’s happening in the second decade of the 21st century.

Rock ’n’ roll was built, in part, on something that would today be classified as “cultural appropriation.” But as exploitative and abusive as the process often was, it could also be collaborative and inspirational. Without it, we would never have had Elvis or the Stones or thousands of other acts that enriched our listening and our culture over the second half of the 20th century. The result was greater cultural appreciation. In retreating to our respective political and artistic corners, we’re losing that appreciation, and with it our empathy for those who aren’t like us.

This isn’t about being “colorblind.” Just the opposite: It’s about being open to hearing the many voices that are spoken, rapped or sung in a rich tapestry of American tradition that belongs to all of us, not just those on the streets of the Motor City or the rural routes outside our mythical Mayberry.

Rock ’n’ roll was revolutionary, but it also brought us together, however imperfectly and however fleetingly. Music can do that, which is why the death of rock ’n’ roll as a cultural force in America is something we all should mourn.