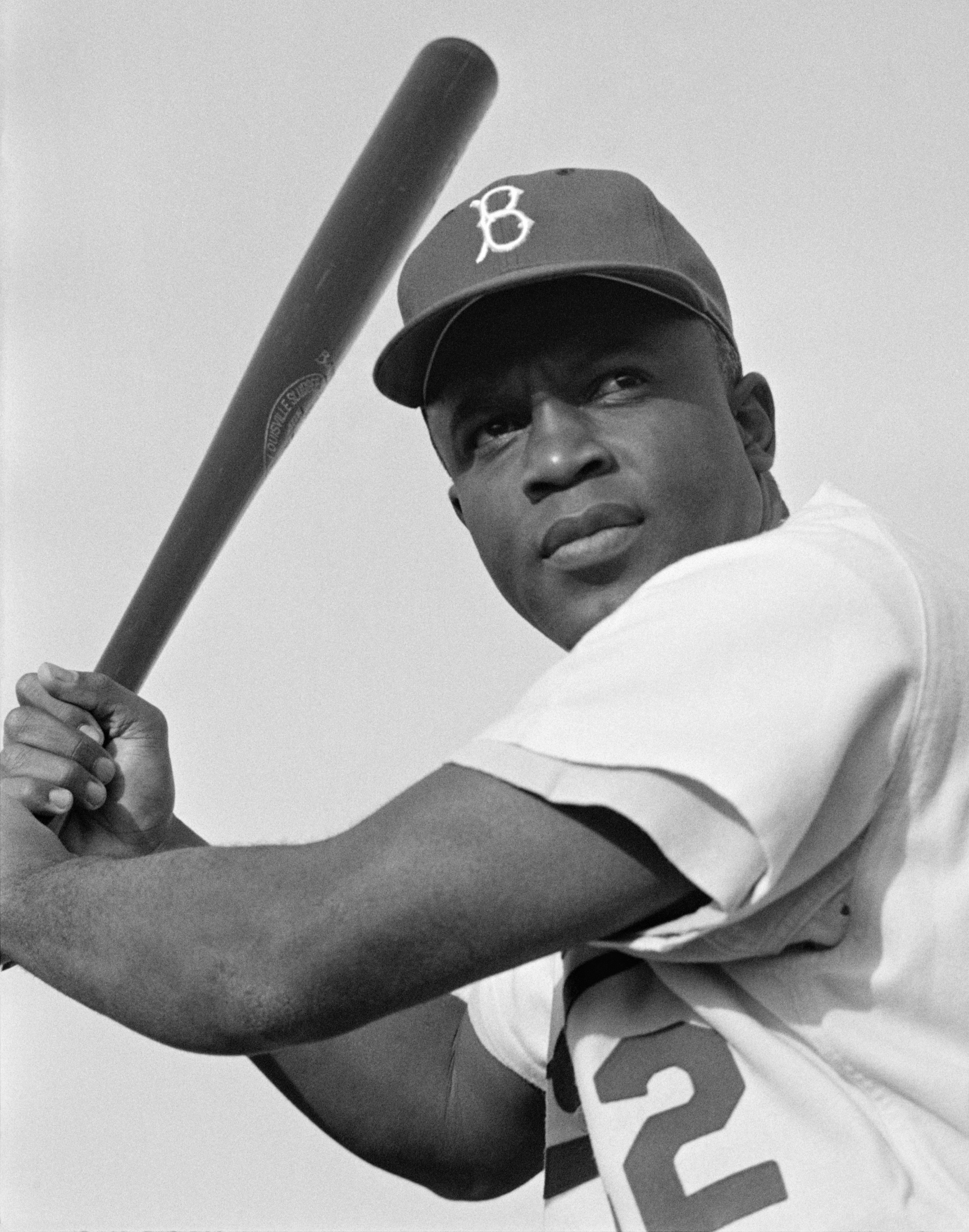

They're not alone. It might surprise some to learn that Jackie Robinson was among those who refused to stand for the anthem. This is the same Jackie Robinson who broke baseball's color barrier and who received an honorable discharge after serving in the Army during World War II.

Robinson wrote in his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had It Made, "As I write this twenty years later (after his first World Series appearance in 1952), I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world."

If Donald Trump wants the NFL to fire players who don't stand for the anthem, would he also evict Robinson from baseball's Hall of Fame?

DISUNITY UNMASKED

The flag and anthem are supposed to be symbols of unity (this is, after all, the United States of America). I can understand why some might object to those they think are disrupting that unity by choosing not to stand for the anthem.

But I would pose the following question: Are these players really causing disunity, or are they simply unmasking it?

True disunity: Assigning 2nd Lt. Jackie Robinson to an all-black unit of the U.S. Army and forcing him to begin his professional baseball career in the segregated "Negro Leagues."

True disunity: Erecting monuments that celebrate the leaders of a secessionist movement that left more than 600,000 people dead and nearly destroyed the country — all for the sake of preserving another form of disunity: slavery.

True disunity: Waving the Confederate battle flag, war symbol of that secessionist movement, 150-plus years later.

Race aside, slavery aside, how is it acceptable to anyone that an American citizen standing for the national anthem should also display a flag that was carried into battle against men who raised the Stars and Stripes?

How can anyone defend such a flag of treason and, at the same time, object to someone kneeling and perhaps bowing his head before a sporting event? Someone who doesn't want to fight, but just wants to be heard. And acknowledged. And valued.

That's what this is about. It's not too much to ask. Indeed, it's exactly what our flag is supposed to represent.