5 reasons I don’t care for hip-hop

Stephen H. Provost

I’d rather do a lot of things than listen to hip-hop. That doesn’t make it bad; it just means I don’t like it.

Read MoreUse the form on the right to contact us.

You can edit the text in this area, and change where the contact form on the right submits to, by entering edit mode using the modes on the bottom right.

PO Box 3201

Martinsville, VA 24115

United States

Stephen H. Provost is an author of paranormal adventures and historical non-fiction. “Memortality” is his debut novel on Pace Press, set for release Feb. 1, 2017.

An editor and columnist with more than 30 years of experience as a journalist, he has written on subjects as diverse as history, religion, politics and language and has served as an editor for fiction and non-fiction projects. His book “Fresno Growing Up,” a history of Fresno, California, during the postwar years, is available on Craven Street Books. His next non-fiction work, “Highway 99: The History of California’s Main Street,” is scheduled for release in June.

For the past two years, the editor has served as managing editor for an award-winning weekly, The Cambrian, and is also a columnist for The Tribune in San Luis Obispo.

He lives on the California coast with his wife, stepson and cats Tyrion Fluffybutt and Allie Twinkletail.

Ruminations and provocations.

Filtering by Tag: Aerosmith

I’d rather do a lot of things than listen to hip-hop. That doesn’t make it bad; it just means I don’t like it.

Read MoreStephen H. Provost is the author of Pop Goes the Metal: Hard Rock, Hairspray, Hooks & Hits, chronicling the evolution of pop metal from its roots in the 1960s through its heyday as “hair metal” in the 1980s and beyond. It’s available on Amazon.

There aren’t many things more subjective than a “best of” music list. And, since I like music — and being subjective, I thought I’d put together my own. My first subject of choice? The rock anthem.

Even the definition of a rock anthem is subjective. A site called DigitalDreamDoor, which compiled its own list, described it as: “a powerful, celebratory rock song with arena-rock sound often with lyrics celebrating rock music itself and simple sing-a-long choruses, chants, or hooks.” I like that definition, so I figured I’d use it as a starting point here.

But be warned: You won’t agree with everything on this list. You won’t find most of the obvious choices here, even if they’re among my favorites. (Examples: “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Born to Run” and “Rock and Roll All Nite.” And no, streetlight people, you won’t find “Don’t Stop Believin’” here, either.)

What you’ll find below are my selections of underappreciated anthems from the 1970s through the new millennium. They’re not necessarily the most popular or most played. In fact, I went out of my way to pick some surprising tracks that probably won’t appear on many lists.

So here goes:

Yeah, it’s a synth riff, but it’s still a killer riff. An almost one-hit-wonder (this Swedish band also charted with “Carrie” from the ’80s), this song was all over MTV in the hair-metal days. But it seldom appears on any list of anthems, so I wanted it on mine.

“The words of the prophets are written on the studio walls.” Indeed. The more obvious choice might be their biggest hit, “Tom Sawyer,” but this one came out a year earlier... and I like it better. I actually like “Freewill” off the same album (“Permanent Waves”) better, but this fit more the definition of an anthem better.

The Ramones came out with the original version of this tune in 1979, but I prefer KISS’ version on the 2003 tribute album, “We’re a Happy Family.” Sure, most KISS fans would choose “Rock and Roll All Nite,” but as iconic as that tune is, I’ve heard it so often I wanted something different, and this cover is surprisingly good, especially since it isn’t from their golden era.

Most people would probably choose “Livin’ on a Prayer,” right? Well, this later selection – from the 1999 release “Crush” is every bit as much of an in-your-face affirmation and just as catchy, in my book. It’s only disadvantage was the fact that it wasn’t included on the mammoth smash CD “Slippery When Wet.” Still, it was a No. 1 hit in Europe.

Confession: This one is a guilty pleasure of a karaoke track for me. I never owned a Loverboy album, and I doubt I ever would, but this track is easily the catchiest and most anthemic song they ever put out. The lead track from their smash sophomore release, “Get Lucky,” it got all the way to No. 2 on the Billboard Album Rock Tracks chart.

Foreigner’s fourth album, aptly titled “4” had two No. 1 Mainstream Rock hits and a No. 3 entry in the form the anthem “Juke Box Hero.” The band never released the album’s other anthem as a single, but it was just as good – better, I think. “I’m Gonna Win” is the perfect soundtrack for anyone determined to overcome an obstacle. That’s why I chose it.

The lead track off Benatar’s “Wide Awake in Dreamland” LP, “All Fired Up” just barely cracked the top 20, peaking at No. 19. It was actually Benatar’s last song to even chart on the Billboard Hot 100. She’s better known for “Love is a Battlefield” and the similarly anthemic “Invincible,” but you’d be hard-pressed to find a more empowering song than this one in her catalog. Or, for that matter, anywhere.

Every bit as catchy as her monster hit “I Love Rock and Roll,” which topped the charts seven years earlier, this tune came from the former Runaway’s sixth album, “Up Your Alley.” It got as high as No. 8, making it her third, and last top 10 hit. A virtuoso at cranking out cover songs that were harder-hitting than the originals, Jett actually co-wrote this one herself, with Desmond Child.

Not as well known as the David Bowie-penned “All the Young Dudes,” this was nonetheless a standout track from the British band, which took it to No. 16 on the UK singles chart. If I had my druthers, I’d go with Def Leppard’s 2006 cover version, but I promised to limit myself to one selection per artist. If I hadn’t, I’d have four or five Def Leppard songs on this list.

I had to include something by Green Day. The only question was whether it would be this one or “Basket Case.” I chose the title track to their 2004 chart-topping album of the same name mainly for the lyrics: “Don't wanna be an American idiot – One nation controlled by the media – Information Age of hysteria – It's calling out to idiot America.” They just didn’t know how bad it would get.

No, not “Get it On (Bang a Gong).” Unlike that one, this far more anthemic selection never was a hit in the states. There’s no accounting for taste. One of the heaviest tunes Marc Bolan and company ever put out, it’s another one that was covered admirably by Def Leppard in 2006. Despite Bolan’s lack of hits in the U.S., T. Rex made it into the Rock and Roll Hall Fame this year – and deservedly so.

Jimmy Eat World was one of my favorite alternative rock bands around the turn of the 21st century, and this was by far their biggest hit, a serenade for anyone who feels like they’ve taken a gut punch from life. “Hey, don’t write yourself off yet. It’s only in your head you feel left out and looked down on.” It hit No. 1 on the Billboard Alternative Songs chart.

I never got into My Chemical Romance, but somehow this song and its follow up, “Desolation Row,” both stuck with me. “Teenagers” only hit No. 67 on the Billboard chart (“Desolation Row” didn’t even make the Hot 100), a far cry from their biggest release, the previous years’ “Welcome to the Black Parade,” which got to No. 9. But a catchier tune is hard to find.

For my money, “Highway to Hell” and “Back in Black” can’t hold a candle to this revved-up rocker off “Powerage,” which didn’t even chart in the U.S. Not that AC/DC ever was a singles band, anyway. Despite that, at my high school, the local album rock station was already playing AC/DC in such heavy rotation I got sick of them. I never got sick of this one, though.

Donnie Iris never looked much like a rocker, even after he stopped going by Dominic Ierace. The guy always seemed like someone had kidnapped Buddy Holly, given him a New Wave makeover, and transplanted him in the 1980s. But looks can be deceiving. This is an amazingly simple but absolutely killer track that was his only Mainstream Rock top 10 entry, at No. 9.

I swear, when this single off the Beastie Boys’ debut album exploded onto the radio in’86, I had no idea they were a hip-hop band. I didn’t even know what hip hop was. This sounded like the epitome of hard rock rebellion, the kind of hook-laden powerhouse that made “We’re Not Gonna Take It” sound like a lullaby. Still, in my opinion, the best thing they ever released.

I confess, I’m a Van Hagar guy. David Lee Roth’s whooping and posing never did it for me. The Red Rocker was a meat-and-potatoes good-time partier who could actually play guitar. And this, just his second top 40 hit on the rock chart, is more of an anthem (closest competition: “Right Now”) than anything he or DLR ever put out with Eddie and Alex.

The album of the same name was, in many ways, a disappointing follow-up to the one-two punch of “Toys in the Attic” and “Rocks.” But the title track was killer. Everyone remembers “Walk This Way,” and rightfully so, but Joe Perry’s guitar riff on this was big enough to carry the whole album. The band was in the twilight of its golden era and had to hit rock bottom before resurrecting itself a decade later.

Def Leppard’s second single off their second album didn’t chart, but I heard it on the radio, and I was sold. It was a close call between this one, “Let’s Get Rocked” and “Rock of Ages” on which would make the list. But this was my first impression of the band, and it definitely stayed with me. Oddly, I never bought this album (“On Through the Night”), but I’ve picked up every one since.

This may be the only “obvious” choice on the list, and it tops many others’ anthem rundowns. But there’s a twist: This is not the album version, it’s a revved-up, double-speed racer from Queen’s double-live “Killers” album, recorded in Montreal four years after the studio version came out. It’s even more of a balls-out rocker than the original. That’s why it’s on the list.

Yes, this is obscure. This New Orleans-based band never placed even one single on the charts, but they did put out a handful of sophisticated yet hard and heavy albums in over the years. This particular tune got into rotation on MTV. It was a cover of the old Badfinger hit, and – as much as I love Badfinger – it just blows the original away. It’s even better than Def Leppard’s cover, which is saying something.

It’s odd, in a way, that Zep didn’t put out any anthems. Some folks might cite “Rock and Roll” as their definitive contribution to the style. But I’d put this one ahead of it. Robert Plant’s opening wail is rivaled only by Paul Stanley’s for Kiss’ “Heaven’s On Fire,” and the rest of “Immigrant Song” doesn’t let up a bit. It sounds just like a Viking invasion, and the line “hammer of the gods” became a signature for the band.

For many U.S. fans, the Sweet-est anthem might be “Ballroom Blitz.” U.K. fans would probably prefer “Block Buster.” Either would be a worthy choice. But this track off “Give Us a Wink” really cemented Sweet’s status as more than bubblegum rockers. Unfortunately, the band went downhill shortly thereafter, hindered by the (now late) lead vocalist Brian Connelly’s substance abuse.

Weezer isn’t the kind of band you’d expect to put out an anthem, but when they decided to do so, they hit it out of the park. You won’t find this song on any of their albums. They dropped it free on iTunes in 2010 to mark the U.S. soccer team’s first meeting with England in 60 years. The song is dripping with fist-pumping swagger. Oh, the game? It ended in a 1-1 draw.

I’m from the Classic Rock era, but like my No. 2 choice, this isn’t a Classic Rock arena anthem. I couldn’t name another Muse song if you asked me, but this is darn near the perfect anthem. “Uprising” hit No. 1 on the Alternative Songs chart, fueled by some of the most defiant lyrics: “They will not force us. They will stop degrading us. They will not control us. We will be victorious. (So come on!)”

Top photo: KISS in 2013, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen H. Provost is the author of Pop Goes the Metal: Hard Rock, Hairspray, Hooks & Hits, chronicling the evolution of pop metal from its roots in the 1960s through its heyday as “hair metal” in the 1980s and beyond. It’s available on Amazon.

What happened to rock ’n’ roll?

Elvis Presley and the Beatles were larger-than-life icons who created transcendent music, but a half-century after Beatles released their signature “White Album,” the genre seems anything but transcendent.

In his book Twilight of the Gods, Steven Hyden suggests that classic rock began with the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967 and ended with Nine Inch Nails The Fragile in 1999. (Apparently, NIN’s previous album title, The Downward Spiral, had been prophetic.) The model makes as much since as any, although I might push the death of the genre to 2003’s American Idiot by Green Day. but regardless, the question remains: Why did a genre of music that prided itself on burning out, instead just fade away?

Jimmy Page playing with Led Zeppelin in Chicago, mid-1970s.

For a while, rock looked invincible. It survived the onslaught of disco, which dominated radio in the late 1970s only to come crashing down at the end of that decade. But disco was ill-equipped to challenge rock ’n’ roll, because it was a different kind of animal.

Disco was all about white pants suits, Studio 54, excess and hedonism. It was jet-setting on a dancefloor. Rock, at its core, had never been about any of that. It had always been about rebellion, so when disco got too popular, rock ’n’ roll was equipped to fight back with bare knuckles and no holds barred. Rockers wore “Death to Disco” T-shirts to school, and in July of 1979, thousands of disco albums were blown up on Disco Demolition Night at Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

It was the beginning of the end for disco, but it also showcased the limitations of rock. As time passed, the music revolution of the 1960s lost its edge. Zeppelin broke up. The Who launched a seemingly endless series of farewell tours. The hope of a Beatles reunion died on December 8, 1980. Queen ended its self-imposed ban on synthesizers. KISS took off its makeup.

The music itself became more closely associated with middle-aged, middle-class nostalgia and aging hipsters than with anything close to the cutting edge. Seattle-based grunge gave it a brief jolt in the early ’90s, but it was only a temporary reprieve. First punk (in the late ’70s and early ’80s) then rap became the music of real rebellion, and rock was left to relive past glories on the fair circuit and classic rock radio.

Even new bands are following the same old formula. The Struts sound a lot like Queen with a dash of Oasis. Greta Van Fleet sounds like Zeppelin. As good as their music might sound (and it does sound good to classic rock aficionados like yours truly), it’s following a familiar template rather than attempting to create something groundbreaking, the way NIN did with The Fragile or Green Day did with American Idiot.

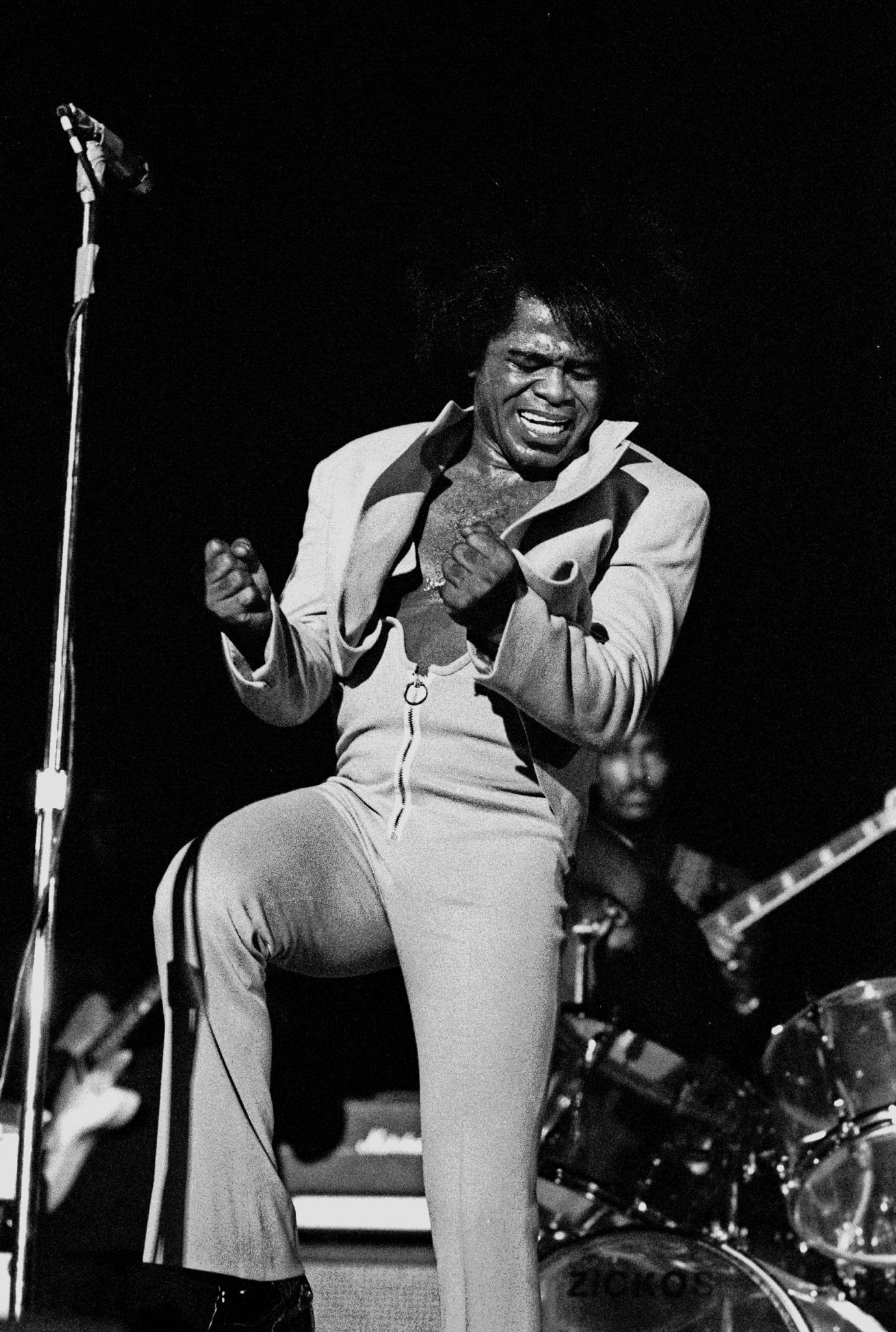

James Brown, Hamburg, 1973.

That’s a fairly standard explanation for the decline of rock, but there’s something more fundamental than decaying relevance and generational change at work here. There’s musical re-segregation. Rock ’n’ roll was the product of a nation getting ready to integrate black and white cultures. Elvis’ first number one single, Heartbreak Hotel, hit the charts barely two months after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Elvis and other white artists brought black rhythm and blues into the mainstream. The British Invasion is a misnomer: The blues invaded Britain first, then was sent back to the States courtesy of the Stones, the Animals, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall, Eric Clapton and others. Soon, black performers themselves were also in the spotlight via Motown, James Brown, the Supremes, the Miracles, Chuck Berry, et. al.

But white performers didn’t just borrow – or, in many cases, steal – R&B. They fused it with country, western swing and rockabilly to form something entirely new that was a reflection of a society experimenting with integration after decades of bigotry. Jackie Robinson had integrated baseball. Kenny Washington had integrated football. Brown v. Board of Education had integrated schools.

Now it was music’s turn. Rock ’n’ roll was to music what Brown was to legal precedent: It upended everything. But today, it barely survives.

The emergence of rap/hip-hop didn’t stop it, initially at least. Blondie recorded Rapture in 1980, Run-DMC covered Aerosmith’s Walk This Way five years later (with Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry guesting on the track). Kid Rock’s Devil Without a Cause in 1998 was an amalgam of good ol’ boy country music and inner-city rap that worked to the tune of 14 million in sales. Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory in 2000 has sold 30 million copies and remains the best-selling rock album of the new millennium.

The late Chester Bennington of Linkin Park, performing in 2014.

But as the music industry became fragmented, the segregation of the pre-Elvis era began to reassert itself. As rock went into decline, listeners turned to either hip-hop or rejuvenated (and more electrified) country music. Some hip-hop artists incorporated or sampled elements of rock, and some country artists did the same, but these days, rock tends to be the seasoning rather than the main ingredient. Most country fans have no use for hip-hop, and most hip-hop fans disdain country.

This new musical segregation reflects the nation at large. It’s not just about race. More fundamentally, the growing musical dichotomy reflects the widening cultural and political gap between urban and rural realities, a growing mutual isolation (and distrust) fed by an increased boutique approach to the arts.

Just as access to specialized news outlets has furthered the divide between liberals and conservatives, the same development has widened the gap between rural and urban artistic expression. The more easily we can get our ears on something we like, the more likely we are to ignore or disparage something that sounds foreign, and that’s just what’s happening in the second decade of the 21st century.

Rock ’n’ roll was built, in part, on something that would today be classified as “cultural appropriation.” But as exploitative and abusive as the process often was, it could also be collaborative and inspirational. Without it, we would never have had Elvis or the Stones or thousands of other acts that enriched our listening and our culture over the second half of the 20th century. The result was greater cultural appreciation. In retreating to our respective political and artistic corners, we’re losing that appreciation, and with it our empathy for those who aren’t like us.

This isn’t about being “colorblind.” Just the opposite: It’s about being open to hearing the many voices that are spoken, rapped or sung in a rich tapestry of American tradition that belongs to all of us, not just those on the streets of the Motor City or the rural routes outside our mythical Mayberry.

Rock ’n’ roll was revolutionary, but it also brought us together, however imperfectly and however fleetingly. Music can do that, which is why the death of rock ’n’ roll as a cultural force in America is something we all should mourn.