3 sayings that could really make America great again

Stephen H. Provost

“Don’t tell me what to do!”

But I’ll damn well tell YOU what to do! And you’d better do it, or else!

That’s become the prevailing attitude in new-millennium America. Anti-maskers whine and moan about freedom to do what they want — then rip off other people’s masks and belittle them for expressing their freedom to do the opposite.

We want the freedom to have sex with whoever we want, as long as it’s between consenting adults. Unless those adults are gay or lesbian. Then they shouldn’t be allowed to have sex, or even kiss in public. And heaven forbid they get married... even though none of what they do affects us in the slightest.

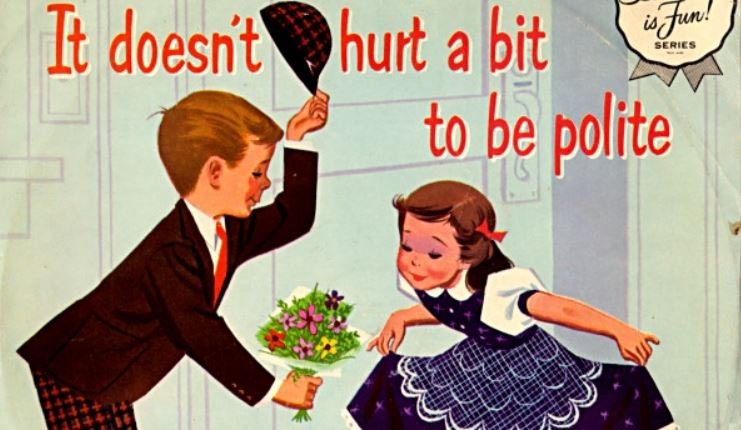

We want things our way, and we want everyone else to do things our way, too. Controlling and micromanaging others (or degrading and bullying them if they fail to go along) has become a hallmark of modern American society. It’s quite a contrast to the America I grew up in, where my parents’ sense of civility still ruled the day, even as the civil rights movement expanded the sense of equality and respect to levels our nation had never seen before.

Today, the opposite is happening: Civil rights are being threatened, and civility is all but a thing of the past.

The breakdown of civility has been written about extensively with regard to our political system, but it reflects a much more fundamental breakdown in the social norms that underpinned our culture for so long. Those norms can be expressed in just five words:

Please.

Thank you.

You’re welcome.

We could really start making America great again if we remembered how to use them.

Not taking no for an answer

In our thirst to control others and force them to submit to our will, we’ve abandoned any semblance of politeness and respect. Instead of asking people for help, we order them around like Sergeant Carter on an old episode of Gomer Pyle. Then we belittle and condescend to them like Jack Nicholson’s colonel in A Few Good Men shouting, “You can’t handle the truth!”

Even as we agree, superficially, with the concept that “no means no” (which applies to sexual consent, but much more as well) we applaud those who refuse to take no for an answer. Because they’re “strong.” They’re “independent.” They won’t be pushed around. Case in point: the tape of Donald Trump bragging about grabbing women’s private parts and kissing them without permission. At the time, pundits were shocked that Trump survived the scandal, yet he not only survived but won the election (albeit despite losing the popular vote).

It’s not merely that people voted for Trump despite his refusal to take no for an answer; some people likely voted for him because of it. They admired him for imposing his will on someone else, as abhorrent and disgusting as that is.

Because they want to do the same thing. Not necessarily with women, but with people in general.

The fact is, we as a society have given up on civility and decided we’d rather force other people to do what we want — even when their actions don’t directly affect us.

Left, right, left

It’s not just the Trumpists, either. The left does it, too. Instead of simply saying no and refusing to accept a sexist, racist, or otherwise inappropriate comment, they go nuclear and ruin people’s careers. They insist that one such comment is enough to define the entirety of who that person is. Nothing else they’ve done matters, whether they’ve given money to charity, worked at a soup kitchen, or helped a little old lady across the street.

The focus is on punishing people, giving them modern-day scarlet letters and blackballing them, not on solving problems.

On that front, I don’t blame the right for being angry.

Just like I don’t blame the left for being angry when the right tries to restrict voting rights or spread a deadly disease in the name of freedom.

But anger doesn’t solve any problems, because it just leads everyone to become more controlling, more demanding, and less willing to accept no for an answer. On anything.

The irony of this is that civility and compassion will get us what we want a lot more easily than intransigence and bullying will. Take the abortion issue, for example. I very seldom even talk about abortion because of its polarizing nature. But I will say this: The best way to reduce abortion isn’t to throw women or doctors in jail; it’s to provide financial aid for low-income women. Three-quarters of women who get abortions are low-income.

Yet solutions have taken a back seat to the use of force. Heaven forbid you actually help the mother and the child. Reducing abortions isn’t what’s important to many political opportunists claiming to be pro-life, or they’d be providing more help to women in poverty. Again, punishment (and the feeling of superiority that goes with it) is what matters to them. And if you want to argue that financial aid costs money, I’ll counter that if money’s more important to you than a human life, you’re really not pro-life at all. Besides, prison time costs taxpayers a ton of money, so, frankly, I don’t buy it.

Ask, don’t tell

If we really wanted to solve problems, we wouldn’t be all about punishment and the use of force. We’d be asking people instead of telling them. Believe it or not, that gets better results.

The blog Relationship by Design put it like this: “When I’m told what to do... I feel small, insignificant, and stupid. I don’t like that feeling, and chances are great that I won’t do what I was told to do anyway, because it becomes a duty, a have-to, or an order in my mind. I don’t take orders well. On the other hand, if I am asked, I will do almost anything. I will put my heart and soul into the request and go above and beyond expectations. And I will feel fantastic about having the opportunity to help someone.”

I’m the same way. Like most people, I don’t like to be told what to do. If you are an expert in a certain field, that’s one thing: I’m likely to follow a chef’s recipe or a doctor’s advice (notice I didn’t call it “doctor’s orders”), because I recognize that person’s expertise. But if you’re telling me what to do — especially for your own benefit rather than the common good or to help me out — I’m not going to be so eager to help. I’ll either refuse or, if you have the means to force my compliance, do so grudgingly.

I’ll probably do a half-assed job, too, either to spite you or simply because I’m not personally invested in your goals. And it’s not too likely I’ll offer to help you out in the future. If you don’t recognize my right to say no, why should I offer to say yes?

Magic words

There are times when quick demands are appropriate: “Get out of the house! It’s on fire” or “Don’t touch that stove! The burner’s on!” come to mind. But those are the exceptions, rather than the rule, and they’re uttered quickly because time is of the essence.

Otherwise, during the course of everyday living, it’s simple enough to preface a request with “Please,” or “Would you mind?” In doing so, you empower the person to say no and, in doing so, make it more likely they’ll say yes. People will go out of their way for a friend; they won’t do so if they’re being treated like a servant or a private in boot camp.

“Thank you” is also important, because it acknowledges a person’s help and further empowers them by affirming that they’re important. It also signals that the task you’ve requested has been completed, so they don’t feel like they owe you anything more. It brings things full circle. Almost.

But there’s one final step in the process: “You’re welcome.” This indicates that you’re pleased to have helped and that you did so of your own free will, not out of compulsion. It confirms the fact that asking was the right thing to do and reinforces the importance of mutual respect in this kind of interaction. Simply saying “OK,” or “whatever” doesn’t accomplish the same thing. (Of course, “you’re welcome” can imply that the person is welcome to ask you again. If that’s not the case, you can still achieve the same result by saying something like “I was happy to do it.”)

And here’s a bonus: actually apologizing when you’ve done something wrong. That’s something else Trump never does, because (to his mind) it makes him look “weak.” The truth is, it takes guts to own up to a mistake, something Trump and his ilk don’t have. They’d rather peddle an alternate reality in which they’re never wrong and force people to believe in it, even though they know it’s absurd.

Asking politely. Apologizing. Expressing thanks. These kinds of interaction came to be almost automatic in my parents’ generation — so much so that it was almost taken for granted. But in abandoning it, we’ve sacrificed much of the power we’ve been seeking to assert by compelling others to do meet our demands.

Controlling and demanding is a lose-lose situation, but it’s what happens when we refuse to take no for an answer. Unfortunately, that’s all anyone seems to be doing these days.

Stephen H. Provost is an author and former career journalist who has written 40 books on topics ranging from history to politics and in genres including fantasy and paranormal fiction. His works are all available on Amazon.