On Nov. 23, 1984, a young quarterback from Boston College threw a pass that will be forever engrained in the minds of college football fans.

Trailing by four points and down to his last play, Doug Flutie dropped back to pass, scrambled around, and heaved a Hail Mary pass from his own 37-yard line. Flutie was small for a quarterback – just 5 feet, 9 inches – and he had already thrown the ball 45 times during the game. Throwing into a 30 mph wind, there was no way he could get the pass all the way to the University of Miami’s end zone.

Or so Miami’s defensive backs thought: Three of them moved up in front of the goal line, positioning themselves to intercept Flutie’s pass … which instead sailed over their heads and into the waiting arms of Boston College receiver Gerard Phelan.

The touchdown gave Boston College a 47-45 win on national television, and Flutie went on to win the Heisman Trophy, presented each year to the best player in college football.

After Flutie graduated, he had a chance to sign a contract with the Los Angeles Rams of the NFL, but he chose a different course. There was, at the time, a second professional football league: the United States Football League (USFL), which played its games in the spring, and the man who owned that league’s New Jersey Generals franchise was offering Flutie an $8.3 million contract.

That man was real estate tycoon Donald Trump – the same man who would win the Republican nomination for president of the United States in 2016. He was relatively unknown then, outside of the Eastern Seaboard, and ownership of the Generals catapulted him to national prominence.

Flutie’s folly?

Why did he sign Flutie? Despite his college success, pro scouts tend to shy away from quarterbacks shorter than about 6-foot-2. They have a harder time seeing over the line, and they often have to scramble around a lot – as Flutie did on that Hail Mary play – to get a good look downfield. Seattle’s Russell Wilson, who’s 2 inches taller than Flutie, has been one of the few quarterbacks shorter than 6 feet tall to have success as a pro.)

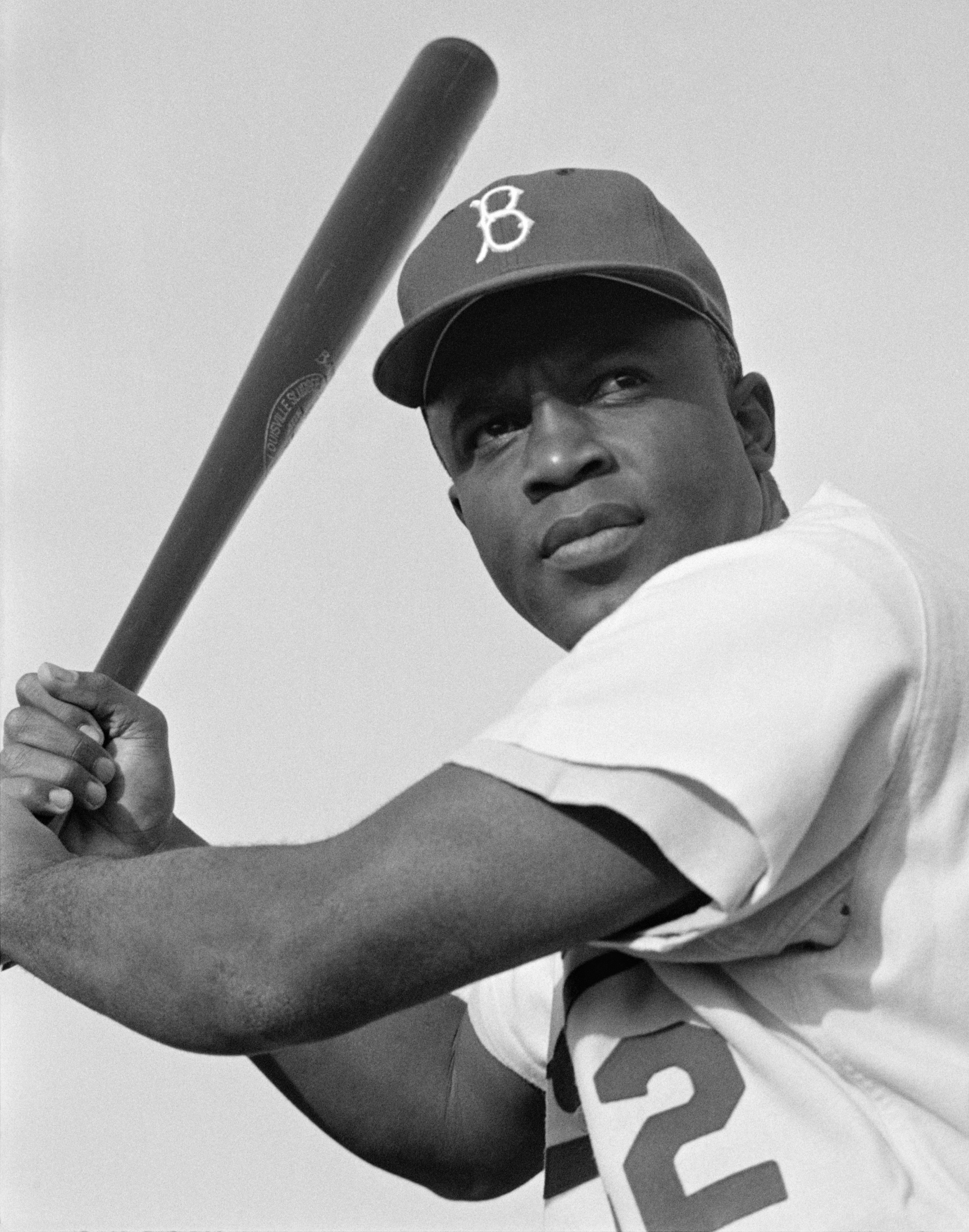

The Generals’ coach at the time, Walt Michaels, wanted to draft Randall Cunningham, an African-American quarterback out of UNLV who stood 6-3 and was a better quarterback than the scrambling Flutie. He would go on to throw for 207 touchdowns and run for 35 more, winning the Most Valuable Player award twice in a 16-year NFL career.

Flutie, who wound up throwing more interceptions than touchdown passes in just one season for the Generals, only played more than seven games in an NFL season five times, although he did put up some big numbers during eight seasons in the Canadian Football League.

But Flutie had what Trump was looking for (and Cunningham lacked). He had golden-boy looks – think Tom Cruise or Steve Garvey – a marketable name and a reputation for doing the impossible: three things Trump saw in himself. And if you get Donald Trump to look in a mirror, you’ve got his attention, just as surely as if he were the evil queen from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

Trump’s own golden boy looks have faded to orange since then, but he’s defined himself based on those other two qualities he shared with Flutie back in 1984. He’s put his name on everything from steaks to casinos, and he has repeatedly tried to do the impossible.

Far more often than not, he’s failed.

Six bankruptcies related to his resorts and casinos, and a portfolio littered with bad ideas and shuttered businesses. Trump Airlines. Trump casinos. Trump Magazine. Trump Mortgages. Trump University. Trump Vodka. Trump the Game.

Using the USFL

And then there was the USFL. The league had been founded in 1983 on a business model geared toward meeting a demand for football during the spring, after the NFL had completed its season, and using a salary cap to operate on a tighter budget. It made some sense: Don’t go head to head with the big boys, who have more money, an established reputation and a huge fan base. Instead, build your own brand in a different niche.

But some of the league’s owners soon abandoned the league’s frugal model in a race for big-name players, signing them to outsized “personal services” contracts as a way around the salary cap. They paid the price for opening up their wallets when revenues failed to keep pace with salary demands.

About the same time Flutie was making a splash during his senior year at Boston College, Trump was urging USFL owners to abandon the other major component of their business plan and throw a Hail Mary pass of their own by ditching the spring-season format and going head-to-head with the NFL in the fall.

With the red ink already rising on their ledgers, the league was hardly in a position to mount a realistic challenge to the sport’s burgeoning behemoth, so Trump hatched a plan to sue the NFL under U.S. antitrust laws, claiming it was acting as a monopoly.

A jury did indeed find in favor of the USFL, but it also found that the league had switched to a fall schedule, not in order to save itself, but to force a merger with the NFL. The result? The jury awarded the USFL just $1 in damages (trebled to $3 under rules applied to antitrust lawsuits), effectively putting the league – and Trump’s team – out of business.

His Hail Mary had fallen flat. As with his bankruptcies, he had no choice but to forfeit the game.

Shifting the blame

Trump, however, blamed the league’s other owners, writing in The Art of the Deal, “If there was a single key miscalculation I made with the USFL, it was evaluating the strength of my fellow owners.”

Trump’s handling of the USFL became the template for his strategy in business and in life: Promise great things, throw a Hail Mary pass, and hope it works. Then, when it falls incomplete and the clock runs out, blame the referee. Or the other team. Or your fans. Or anybody, except yourself for taking such an outrageous risk in the first place.

No matter how many times we might enjoy watching replays of Doug Flutie throwing that magical pass against Miami, he only did it once. Trump has had successes, but with the exception of TV’s “The Apprentice,” they’ve all been in a single arena: real estate – an industry in which he’s also seen plenty of failure even though his father paved the way for him with both capital and presumed know-how.

Trump knows something about real estate. But he doesn’t know anything about vodka, or universities, or airlines, or football.

Or governing.

The thrill of the hunt

When he entered the 2016 presidential race, Trump was just launching another Hail Mary pass in a game he knows nothing about. All that’s important to him is that it’s a game. “It’s all about the hunt,” he was quoted as saying in Timothy O’Brien’s 2005 book TrumpNation, “and once you get it, it loses some of its energy. I think competitive, successful men feel that way about women.”

It there’s a clearer way of saying that women are a piece of meat without coming right out and using those words, I don’t know what it is.

The quote not only speaks volumes about Trump’s predatory attitude toward women, as reflected in the 2005 tape from Access Hollywood that sent his presidential campaign floundering, it says something even bigger about his attitude toward life. It’s not just women who are trophies; it’s everything. When Trump says he loves women, he’s not lying; he just “loves” them in the same way Teddy Roosevelt loved bagging a lion, an elephant or a black rhino. He “loves” business associates and voters the same way. No wonder he has so few close friends.

It’s noteworthy that his sons have taken after him in the literal sense, becoming big-game hunters.

Trump’s obsession with the hunt explains why he starts ventures that quickly fail: He has neither the patience nor the inclination to see them through to the end, whether they be a marriage, an investment in a football team or an airline. He loses interest, and he’s on to the next thing. He’s like Alexander the Great or Genghis Khan: so consumed with conquest that he undermines any opportunity for lasting success, because he doesn’t really care about it.

Hail Mary presidency

Other than real estate and “The Apprentice,” he’s seldom stuck with anything long enough to make it work. Now imagine that attitude applied to the presidency. If he were to be elected and follow his familiar pattern, he would quickly lose interest and turn his attention to other things … then blame others for his – and the nation’s – failures, wash his hands of the whole mess and go on to his next big promise. His next Hail Mary.

Or maybe he’d use the office of the presidency as the platform to launch his next campaign for conquest, whether it be a war, an overhaul of the Constitution, an assault on civil liberties or his already-stated objective of building a $12 billion wall … and making Mexico pay for it. Sometimes, it’s hard to tell whether his last name is really Trump or Quixote.

But it doesn’t matter how outlandish his goals seem or how impossible. Remember, he’s all about throwing up Hail Marys to prove he can do the impossible. And this penchant is precisely what makes him so dangerous: It actually behooves him, for the sake of his ego, to create crises so he can set the stage for the adrenalin rush he gets if he manages to solve them. The more desperate the situation looks, the better.

Forget me not

This helps explain why Trump isn’t about keeping promises or taking responsibility for his failures. He famously never apologizes, because he’d be doing it all the time – and because he’s too busy looking in the mirror and talking about how wonderful he is.

And he’s so convinced of it, people believe him.

We still remember Doug Flutie, even though he never won a Super Bowl and spent much of his NFL career as a backup, because he threw that crazy pass against Miami and it worked.

“Without the Hail Mary pass, I think I could have been very easily forgotten,” Flutie would say later.

If we watch that pass over and over again and ignore his NFL career, we might come to believe that Flutie was the best quarterback ever to play the game. And if we listen to Donald Trump tell us he can “make America great again” often enough, we might believe that, too.

That’s what he’s counting on. And once we accept his proposal, the hunt will be over. We’ll be just another trophy for his wall – mounted, stuffed and displayed for all to see. Except no one will be looking at us anymore, because Trump demands that everyone look at him. We’ll be forgotten on the sidelines of history, just like the old New Jersey Generals, while Trump is off on the prowl, looking for his next conquest.

In any hunt, you have to have a quarry. We’re it. And if Trump bags us, we might as well be dead meat.