You're irreplaceable, no matter what they tell you

Stephen H. Provost

Something touched me deep inside the day the music died. - Don McLean, "American Pie."

The past few days have been difficult.

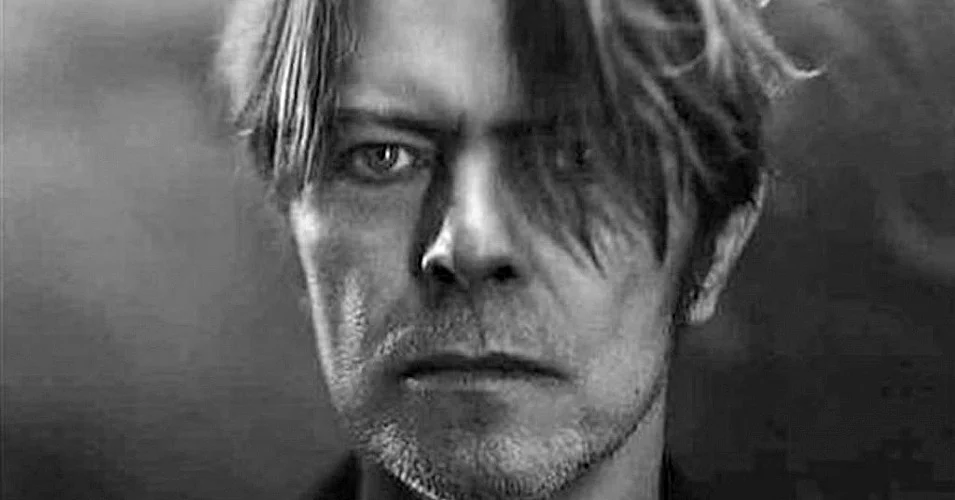

It didn't affect me directly when David Bowie died, but it did affect me personally - as it did when Alan Rickman passed away a couple of days later. I didn't know either of these men. I wasn't a member of any fan club. I never dressed up like Ziggy Stardust, and I wasn't a Rickmaniac.

Both men were British, both were 69 years old and each was profoundly successful in his chosen field. Both died of cancer. But they shared something more than all that, an intangible something that made them, in a word, irreplaceable. Each was unique - fearless in ignoring, stretching and ultimately redefining the boundaries of their chosen professions for the sake being true to themselves.

"Actors are agents of change," Rickman once said. "A film, a piece of theater, a piece of music, or a book can make a difference. It can change the world."

"I don't know where I'm going from here," Bowie said, "but I promise you it won't be boring."

The sadness I felt at their passing had nothing to do with the fact that I'll never hear Bowie perform "The Man Who Sold the World" again or that I'll never see Rickman reprise his role as Severus Snape in some hypothetical "Harry Potter" prequel. It stemmed instead from the realization that I'll never witness them explore new creative challenges, which I have no doubt they would have met with the same finesse and originality they displayed in their previous work.

When a creative soul dies, it's as if creation folds back in on itself, curls into a fetal position and weeps. That's what I felt like doing because, in a sense, the music died again with Bowie. Just as it had with Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens in that plane crash 57 years ago. Just as it did again on Dec. 8, 1980, when John Lennon was shot. And when Freddie Mercury died. And Elvis. And so many others.

I can tell myself it's resurrected every time their songs are played and it's reimagined every time a new, vital artist comes along to stretch the boundaries in new and undreamt-of directions.

But that doesn't make the loss any less painful. Any less personal.

As if those losses weren't enough to deal with this week, I also learned that some people I knew had been laid off. They aren't celebrities, like Bowie or Rickman, but when I heard they'd lost their jobs, it felt no less profound to me.

I imagined them going to exit interviews and being being fed that same old half-excuse, half-apology: "Don't take it personally. It's just business."

I have no idea whether these words were spoken in their cases, but they've been used often enough that they've become a cultural cliche, a way for us to console ourselves when we hurt someone. When we leave a relationship. When we hand someone a layoff notice. When we cut someone from the team. We tell them not to take it personally because we don't want to feel personally responsible for the pain we're inflicting.

But just what are we implying?

That to us, the person on the other end of our rejection was never a person in the first place. He or she was just a position, an impersonal cog in a malfunctioning machine that needs to be removed for the sake of efficiency. An obsolesce at best; a mistake at worst. And now it's time to get "leaner and meaner," with the emphasis on "meaner."

I can't think of anything meaner than treating someone as less than a person, more cruel than chastising him or her for having the audacity to take it personally when you've turned their personal lives upside down.

Of course, it's personal.

And here's the thing: Each of those people - each and every one of us, in fact - is irreplaceable. No less so than David Bowie or Alan Rickman. Each of us has it within ourselves to stretch boundaries, to imagine new vistas, to change at least some part of our world forever. And each time we tell someone, "It's nothing personal," we spit in the face of a unique, creative soul with boundless capacity to make a lasting impact on the future.

As a creative person, an author, I feel we have a basic obligation to nurture one another's artistry and to affirm each individual's personhood.

On the other hand, I count it a tragedy when we dehumanize people to assuage our own guilt or protect our bottom line. It's as if we're thumbing our noses at the people like David Bowie, Alan Rickman and all the other artists who've challenged and inspired us. By depersonalizing them in our own minds, we're eating away at our own humanity, our sense of empathy, our very souls.

All of this makes me very angry; I think I have a right to be.

And yes, I take it personally.